- Home

- Liu Xiaobo

No Enemies, No Hatred

No Enemies, No Hatred Read online

NO ENEMIES, NO HATRED

No Enemies, No Hatred

SELECTED ESSAYS AND POEMS

LIU XIAOBO

EDITED BY

PERRY LINK, TIENCHI MARTIN-LIAO, and LIU XIA

WITH A FOREWORD BY

VÁCLAV HAVEL

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

2012

Copyright © 2012 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Originally published as Ich habe keine Feinde, ich kenne keinen Hass, copyright © S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 2011.

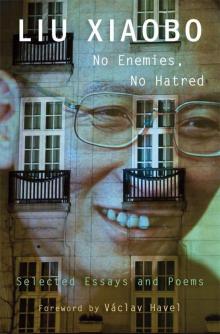

Jacket image: Odd Andersen/AFP/Getty Images

Jacket design: Jill Breitbarth

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Liu, Xiaobo, 1955–

No enemies, no hatred : selected essays and poems / Liu Xiaobo ; edited by Perry Link, Tienchi Martin-Liao, and Liu Xia ; with a foreword by Václav Havel.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-674-06147-7 (alk. paper)

I. Link, E. Perry (Eugene Perry), 1944– II. Martin-Liao, Tienchi. III. Liu, Xia, 1959– IV. Title.

PL2879.X53A2 2012

895.1'452—dc22 2011014145

CONTENTS

Foreword

by Václav Havel

Introduction

by Perry Link

PART I. POLITICS WITH CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS

LISTEN CAREFULLY TO THE VOICES OF THE TIANANMEN MOTHERS

Reading the Unedited Interview Transcripts of Family Members Bereaved by the Massacre

Poem: Your Seventeen Years

Poem: Standing amid the Execrations of Time

TO CHANGE A REGIME BY CHANGING A SOCIETY

THE LAND MANIFESTOS OF CHINESE FARMERS

XIDAN DEMOCRACY WALL AND CHINA’S ENLIGHTENMENT

THE SPIRITUAL LANDSCAPE OF THE URBAN YOUNG IN POST-TOTALITARIAN CHINA

Poem: What One Can Bear

Poem: A Knife Slid into the World

BELLICOSE AND THUGGISH

The Roots of Chinese “Patriotism” at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century

STATE OWNERSHIP OF LAND IS THE AUTHORITIES’ MAGIC WAND FOR FORCED EVICTION

A DEEPER LOOK INTO WHY CHILD SLAVERY IN CHINA’S “BLACK KILNS” COULD HAPPEN

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE “WENG’AN INCIDENT”

PART II. CULTURE AND SOCIETY

EPILOGUE TO CHINESE POLITICS AND CHINA’S MODERN INTELLECTUALS

ON LIVING WITH DIGNITY IN CHINA

Poem: Looking Up at Jesus

ELEGY TO LIN ZHAO, LONE VOICE OF CHINESE FREEDOM

BA JIN

The Limp White Flag

Poem: Alone in Winter

Poem: Van Gogh and You

THE EROTIC CARNIVAL IN RECENT CHINESE HISTORY

Poem: Your Lifelong Prisoner

FROM WANG SHUO’S WICKED SATIRE TO HU GE’S EGAO

Political Humor in a Post-Totalitarian Dictatorship

YESTERDAY’S STRAY DOG BECOMES TODAY’S GUARD DOG

Poem: My Puppy’s Death

LONG LIVE THE INTERNET

IMPRISONING PEOPLE FOR WORDS AND THE POWER OF PUBLIC OPINION

PART III. CHINA AND THE WORLD

BEHIND THE “CHINA MIRACLE”

BEHIND THE RISE OF THE GREAT POWERS

Poem: To St. Augustine

Poem: Hats Off to Kant

THE COMMUNIST PARTY’S “OLYMPIC GOLD MEDAL SYNDROME”

HONG KONG TEN YEARS AFTER THE HANDOVER

SO LONG AS HAN CHINESE HAVE NO FREEDOM, TIBETANS WILL HAVE NO AUTONOMY

Poem: One Morning

Poem: Distance

OBAMA’S ELECTION, THE REPUBLICAN FACTOR, AND A PROPOSAL FOR CHINA

PART IV. DOCUMENTS

THE JUNE SECOND HUNGER STRIKE DECLARATION

Poem: You • Ghosts • The Defeated

A LETTER TO LIAO YIWU

Poem: Feet So Cold, So Small

USING TRUTH TO UNDERMINE A SYSTEM BUILT ON LIES

Statement of Thanks in Accepting the Outstanding Democracy Activist Award

CHARTER 08

MY SELF-DEFENSE

I HAVE NO ENEMIES

My Final Statement

THE CRIMINAL VERDICT

Beijing No. 1 Intermediate People’s Court Criminal Judgment No. 3901 (2009)

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Index

FOREWORD

Václav Havel

IT WAS MORE THAN THIRTY YEARS AGO that we, a group of 242 private citizens concerned about human rights in Czechoslovakia, came together to sign a manifesto called Charter 77. That document called on the Communist Party to respect human rights, and said clearly that we no longer wanted to live in fear of state repression. Our disparate group included ex-Communists, Catholics, Protestants, workers, liberal intellectuals, artists, and writers who came together to speak with one voice. We were united by our dissatisfaction with a regime that demanded acts of obedience on an almost daily basis. After Charter 77 was released, the government did its best to try to break us up. We were detained, and four of us eventually went to jail for several years. Surveillance was stepped up, our homes and offices were searched, and a barrage of press attacks based on malicious lies sought to discredit us and our movement. This onslaught only strengthened our bonds. Charter 77 also reminded many of our fellow citizens who were silently suffering that they were not alone. In time, many of the ideas set forth in Charter 77 prevailed in Czechoslovakia. A wave of similar democratic reforms swept across Eastern Europe in 1989.

In December 2008, a group of 303 Chinese activists, lawyers, intellectuals, academics, retired government officials, workers, and peasants put forward their own manifesto titled Charter 08, calling for constitutional government, respect for human rights, and other democratic reforms. Despite the best efforts of government officials to keep it off of Chinese computer screens, Charter 08 reached a nationwide audience via the Internet, and the number of new signatories eventually reached more than 10,000.

As in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s, the response of the Chinese government was swift and brutal. Dozens, if not hundreds, of signatories were called in for questioning. A handful of perceived ringleaders were detained. Professional promotions were held up, research grants denied, and applications to travel abroad rejected. Newspapers and publishing houses were ordered to blacklist anyone who had signed Charter 08. The prominent writer and dissident Liu Xiaobo, a key drafter of Charter 08, was arrested, and in December 2009 he was sentenced to eleven years in prison.

Despite Liu’s imprisonment, his ideas cannot be shackled. Charter 08 has articulated an alternative vision of China, challenging the official line that any decisions on reforms are the exclusive province of the state. It has encouraged younger Chinese to become politically active, and boldly made the case for rule of law and constitutional multiparty democracy. And it has served as a jumping-off point for a series of conversations and essays on how to get there.

Perhaps most important, as in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s, Charter 08 has forged connections among different groups that did not exist before. Prior to Charter 08, “we had to live in a certain kind of separate and solitary state,” one signatory wrote. “We were not good at expressing our own personal experiences to those around us.”

Liu Xiaobo and Charter 08 are changing that, for the better.

Of course, Charter 08 addresses a political milieu that is very different from Czechoslovakia in the 1970s. In its quest for economic growth, China has seemed to embrace some features far removed from traditional Communism. Especially for young, urban, e

ducated white-collar workers, China can seem like a post-Communist country. And yet China’s Communist Party still has lines that cannot be crossed. In spearheading the creation of Charter 08, Liu Xiaobo crossed the starkest line of all: Do not challenge the Communist Party’s monopoly on political power, and do not suggest that China’s problems—including widespread corruption, labor unrest, and rampant environmental degradation—might be connected to the lack of progress on political reform. And for making that very connection in an all too public way, Liu got more than a decade in prison.

Shortened version of the article by Václav Havel, Dana Němcová, and Václav Malý, “A Nobel Prize for a Chinese Dissident” (2010)

INTRODUCTION

LIU XIAOBO is one of those unusual people who can look at human life from the broadest of perspectives and reason about it from first principles. His keen intellect notices things that others also look at, but do not see. It seems that hardly any topic in Chinese culture, politics, or society evades his interest, and he can write with analytic calm about upsetting things. One might expect such calm in a recluse—a hermit poet, or a cloistered scholar—but in Liu Xiaobo it comes in an activist. Repeatedly he has gone where he thinks he should go, and done what he thinks he should do, as if havoc, danger, and the possibility of prison were not part of the picture. He seems to move through life taking mental notes on what he sees, hears, and reads, as well as on the inward responses that he feels.

Luckily for us, his readers, he also has a habit of writing free from fear. Most Chinese writers today, including many of the best ones, write with political caution in the backs of their minds and with a shadow hovering over their fingers as they pass across a keyboard. How should I couch things? What topics should I not touch? What indirection should I use? Liu Xiaobo does none of this. With him, it’s all there. What he thinks, you get.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. For about two decades, the prize committee in Oslo, Norway, had been considering Chinese dissidents for the prize, and in 2010, after Liu Xiaobo had been sentenced to eleven years in prison for “incitement of subversion”—largely because of his advocacy of the human-rights manifesto called Charter 08—he had come to emerge as the right choice. Authorities in Beijing, furious at the award, did what they could to frustrate celebrations of it. Police broke up parties of revelers in several Chinese cities after the award was announced on October 8, 2010. The Chinese Foreign Ministry pressured world diplomats to stay away from the Award Ceremony in Oslo on December 10. Dozens of Liu Xiaobo’s friends in China were barred from leaving the country lest they head for Oslo. Liu Xiaobo’s wife, Liu Xia, although charged with nothing, was held under tight house arrest. Liu himself remained in prison, and none of his family members could travel to Oslo to collect the prize. At the Award Ceremony, the prize medal, resting inside a small box, and the prize certificate, in a folder that bore the initials “LXB,” were placed on stage on an empty chair. Within hours authorities in Beijing banned the phrase “empty chair” from the Chinese Internet.

Liu was the fifth Peace Laureate to fail to appear for the Award Ceremony. In 1935, Carl von Ossietzky was held in a Nazi prison; in 1975, Andrei Sakharov was not allowed to leave the USSR; in 1983, Lech Wałesa feared he would be barred from reentering Poland if he went to Oslo; and in 1991, Aung Sang Suu Kyi was under house arrest in Burma. Each of the latter three prize-winners was able to send a family member to Oslo. Only Ossietzky and Liu Xiaobo could do not even that.

Liu was born December 28, 1955, in the city of Changchun in northeastern China. He was eleven years old when Mao Zedong closed his school—along with nearly every other school in China—so that youngsters could go into society to “oppose revisionism,” “sweep away freaks and monsters,” and in other ways join in Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Liu and his parents spent 1969 to 1973 at a “people’s commune” in Inner Mongolia. In retrospect Liu believes that these years of upset, although a disaster for China as a whole, had certain unintended benefits for him personally. His years of lost schooling “allowed me freedom,” he recalls, from the mind-closing processes of Maoist education; they gave him time to read books, both approved and unapproved. Moreover, the pervasive cynicism and chaos in the society around him taught him perhaps the most important lesson of all: that he would have to think for himself. Where else, after all, could he turn? In this general experience Liu resembles several others of the most powerfully independent Chinese writers of his generation. Hu Ping, Su Xiaokang, Zheng Yi, Bei Dao, Zhong Acheng, Jiang Qisheng, and many others survived the Cultural Revolution by learning to rely on their own minds, and for some this led to a questioning of the political system as a whole. Mao had preached that “rebellion is justified,” but this is hardly the way he thought it should happen.

Chinese universities began to reopen after Mao died in 1976, and in 1977 Liu Xiaobo went to Jilin University, in his home province, where he earned a B.A. in Chinese literature in 1982. From there he went to Beijing, to Beijing Normal University, where he continued to study Chinese literature, receiving an M.A. in 1984 and a Ph.D. in 1988. His Ph.D. dissertation, entitled “Aesthetics and Human Freedom,” was a plea for liberation of the human spirit; it drew wide acclaim from both his classmates and the most seasoned scholars at the university. Beijing Normal invited him to stay on as a lecturer, and his classes were highly popular with students.

Liu’s articles and his presentations at conferences earned him a reputation as an iconoclast even before he finished graduate school. Known as the “black horse” of the late 1980s, seemingly no one escaped his acerbic pen: Maoist writers like Hao Ran were no better than hired guns, post-Mao literary stars like Wang Meng were but clever equivocators, “roots-seeking” writers like Han Shaogong and Zheng Yi made the mistake of thinking China had roots that were worth seeking, and even speak-for-the-people heroes like Liu Binyan were too ready to pin hopes on “liberal-minded” Communist leaders like Hu Yaobang (the Party chair who was sacked in 1987). “The Chinese love to look up to the famous,” Liu wrote, “thereby saving themselves the trouble of thinking.” In graduate school Liu read widely in Western thought—Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Isaiah Berlin, Friedrich Hayek, and others—and began to use these thinkers to criticize Chinese cultural patterns. He also came to admire modern paragons of nonviolent resistance around the world—Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Václav Havel, and others. Although not formally a Christian, or a believer in any religion, he began to think and write about Jesus Christ.

Around the same time, he arrived at a view of the last two centuries of Chinese history that saw the shock of Western imperialism and technology as bringing “the greatest changes in thousands of years.” Through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, China’s struggles to respond to this shock cut ever deeper into China’s core. Reluctantly, Chinese thinking shifted from “our technology is not as good as other people’s” in the 1880s and early 1890s to “our political system is not as good as other people’s” after the defeat by Japan in 1895 to “our culture is not as good as other people’s” in the May Fourth movement of the late 1910s. Then, under the pressure of war, all of the ferment and struggle ended in a Communist victory in 1949, and this event, said Liu, “plunged China into the abyss of totalitarianism.” Recent decades have been more hopeful for China, in his view. Unrelenting pressure from below—from farmers, petitioners, rights advocates, and, perhaps most important, hundreds of millions of Internet users—has obliged the regime, gradually but inexorably, to cede ever more space to civil society.

The late 1980s were a turning point in Liu’s life, both intellectually and emotionally. He visited the University of Oslo in 1988, where he was surprised that European Sinologists did not speak Chinese (they only read it) and was disappointed at how naïve Westerners were in accepting Chinese government language at face value. Then he went to New York, to Columbia University, where he encountered “critical theory” and learned that its dominant st

rain, at least at Columbia, was “postcolonialism.” People expected him, as a visitor from China, to fit in by representing the “the subaltern,” by resisting the “discursive hegemony” of “the metropole,” and so on. Liu wondered why people in New York were telling him how it felt to be Chinese. Shouldn’t it be the other way around? Was “postcolonialism” itself a kind of intellectual colonialism? Liu wrote in May 1989 that “no matter how strenuously Western intellectuals try to negate colonial expansionism and the white man’s sense of superiority, when faced with other nations Westerners cannot help feeling superior. Even when criticizing themselves, they become besotted with their own courage and sincerity.”

His experience in New York led him to see his erstwhile project of using Western values as yardsticks to measure China as fundamentally flawed. No system of human thought, he concluded, is equal to the challenges that the modern world faces: the population explosion, the energy crisis, environmental imbalance, nuclear disarmament, and “the addiction to pleasure and to commercialization.” Nor is there any culture, he wrote, “that can help humanity once and for all to eliminate spiritual suffering or transcend personal limits.” Suddenly he felt intellectually vulnerable, despite the fame he had enjoyed in China. He felt as if his lifelong project to think for himself would have to begin all over from scratch.

These thoughts came at the very time that the dramatic events of the 1989 pro-democracy movement in Beijing and other Chinese cities were appearing on the world’s television screens. Commenting that intellectuals too often “just talk” and “do not do,” Liu decided in late April 1989 to board a plane from New York to Beijing. “I hope,” he wrote, “that I’m not the type of person who, standing at the doorway to hell, strikes a heroic pose and then starts frowning in indecision.”

Back in Beijing, Liu went to Tiananmen Square, talked with the demonstrating students, and organized a hunger strike that began on June 2, 1989. Less than two days later, when tanks began rolling toward the Square and it was clear that people along the way were already dying, Liu negotiated with the attacking military to allow students a peaceful withdrawal. It is impossible to calculate how many lives he may have saved by this compromise, but certainly some, and perhaps many. After the massacre, Liu took refuge in the foreign diplomatic quarter, but later came to blame himself severely for not remaining in the streets—as many “ordinary folk” did, trying to rescue victims of the massacre. Images of the “souls of the dead” have haunted him ever since. The opening line of Liu’s “Final Statement,” which he read at his criminal trial in December 2009, said, “June 1989 has been the major turning point in my life.” Liu Xia, who visited him in prison on October 10, 2010, two days after the announcement of his Nobel Prize, reports that he wept and said, “This is for those souls of the dead.”

No Enemies, No Hatred

No Enemies, No Hatred